How Wine Becomes Rare or Expensive

Not all wine starts out expensive or rare – although some do – but it can become that way over time.

As people consume the bottles of a given vintage, they reduce the number in circulation, making those remaining bottles rarer. The vintage into why certain wines rise in price while others remain at typical market value. When everything falls into a complete and unique harmony to create an exquisite wine. These wines are more likely to grace the dinner table than remain in wine cellars while aging to perfection.

Another cause of rarity or higher price begins at the winery. If the winery only produces 300 bottles of wine, for example, it starts out rarer than one with 4,000 bottles and will often be more expensive.

Fine wines also become more expensive with age, typically because older wines are unique and require decades of aging to reach a perfect complexity. The storage of the wine also plays a significant role in how the aging wine will become.

Verifiable provenance will also make the difference between a wine worth $2,000 and one worth $20,000 or more.

Some wines aren’t fit for consumption, but they are still worth collecting for the age and name alone. Some older wines fit the less common category of being both old and drinkable—a true delight for those who decide to pop the cork. Remember that when the cork is removed, valuable wine is now worth only the palates of the ones sharing the event.

Domaine de la Romanée-Conti

Burgundy is a region of modest winemaking domains. Yet the grand cru vineyards belonging to the world-renowned Domaine de la Romanée-Conti in Vosne-Romanee have been celebrated since before the French Revolution as the source of the region’s most perfect, expensive, and scarce pinot noirs.

The number of bottles from the regions is only around 6 to 7,000 a year. The price of each bottle can reach $30,000. The most exquisite and rare Chardonnay, the elegant Montrachet, takes the palm.

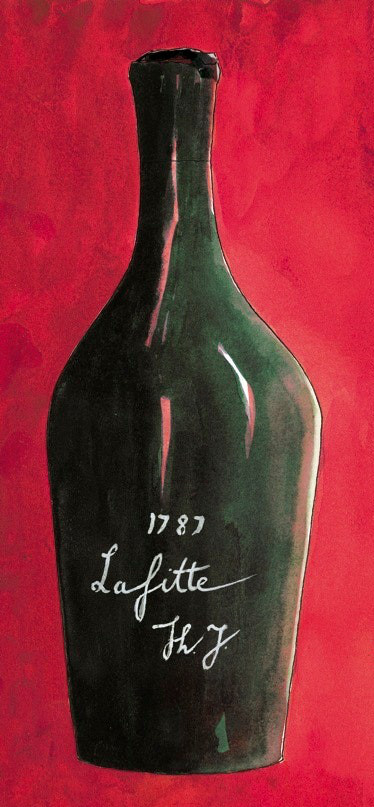

Jefferson Wine

The most expensive bottle of wine ever sold at auction was offered at Christie’s in London on December 5, 1985. The bottle was handblown dark-green glass and capped with a nubby seal of thick black wax. It had no label, but etched into the glass in a spindly hand was the year 1787, the word “Lafitte,” and the letters “Th.J.”

The bottle came from a collection of wine that had reportedly been discovered behind a bricked-up cellar wall in an old building in Paris. The wines bore the names of top vineyards—along with Lafitte (which is now spelled “Lafite”), there were bottles from Châteaux d’Yquem, Mouton, and Margaux—and those initials, “Th.J.” According to the catalog, evidence suggested that the wine had belonged to Thomas Jefferson and that the bottle at auction could “rightly be considered one of the world’s greatest rarities.” The level of the wine was “exceptionally high” for such an old bottle—just half an inch below the cork—and the color “remarkably deep for its age.” The wine’s value was listed as “inestimable.”

There are doubts that the discovery wasn’t the most well-orchestrated scam of them all.